Artistic practice involves movement in two directions: inwards and outwards. Such practice is fueled by the impulse to express yourself in form and language through material. It compels you to think, investigate, use your experience and intuition. At the same time, an artistic practice is inevitably connected to the world in which the artist in question operates, to the outside world: to the relationship that the artist enters into with the environment, with the public, and with other works. Anyone who creates knows how challenging it can be to realize an idea and how vulnerable you have to be for this to happen – and thus comprehends the hurdles involved in completing that outward movement.

REST is the medium through which visual artist Saskia Noor van Imhoff and designer Arnout Meijer maintain and deepen their artistic practice at their new location in Mirns, Friesland. Both creators typically immerse themselves in a chosen subject for extended periods of time, subjects that have included everything from objects to specific materials, pieces of land to the effect of light, and museum spaces to bunkers. Of course, the subject in question is never just ‘something,’ even if it could be almost anything. The point is that many things are worth investigating, contain something worth revealing, worth knowing. REST is new territory for Van Imhoff and Meijer, and represents a new perspective that extends from a landscape of meadows and old forests to the IJsselmeer, the Mokkebank nature reserve, and the Frisian Lakes. The two hectares of reclaimed farmland in the Wielpolder and accompanying 19th-century farmhouse also serve as potential artistic material.

Consequently, REST is a research center, studio, exhibition space, collaborative venture, and living space all rolled into one.

Since the 1960s, artists have explored landscapes as material and settings for sculpture. It’s obvious, when you think about it, that rather than move commonly used sculptural materials such as stone and wood from where we find them, why not simply expose and/or arrange them in situ? What could be more liberating than working in the open, surrounded by nature?

Land art liberated creators from the confines of traditional exhibition spaces, with the natural environment assuming the role of medium and setting, be that temporary or permanent. It also made art accessible in an entirely new way and challenged the conventions of the art world. At the same time, however, land art, particularly its documentation, was also exhibited in institutional settings – precisely because of the physical inaccessibility of certain works. Research on ecological developments and expressions of ecological concerns only emerged later in connection with site-specific artworks.

I am no scientist. I explore the neighborhood. An infant who has just learned to hold his head up has a frank and forthright way of gazing about him in bewilderment. He hasn’t the faintest clue where he is, and he aims to learn. In a couple of years, what he will have learned instead is how to fake it; he’ll have the cocksure air of a squatter who has come to feel he owns the place. Some unwonted, taught pride diverts us from our original intent, which is to explore the neighborhood, view the landscape, to discover at least where it is that we have been so startlingly set down, if we can’t learn why.

— Annie Dillard, Pilgrim at Tinker Creek (1974)

Since the 1960s, artists have explored landscapes as material and settings for sculpture. It’s obvious, when you think about it, that rather than move commonly used sculptural materials such as stone and wood from where we find them, why not simply expose and/or arrange them in situ? What could be more liberating than working in the open, surrounded by nature?

Land art liberated creators from the confines of traditional exhibition spaces, with the natural environment assuming the role of medium and setting, be that temporary or permanent. It also made art accessible in an entirely new way and challenged the conventions of the art world. At the same time, however, land art, particularly its documentation, was also exhibited in institutional settings – precisely because of the physical inaccessibility of certain works. Research on ecological developments and expressions of ecological concerns only emerged later in connection with site-specific artworks.

Agnes Denes, A Forest for Australia, 1998, Altoona Treatment Plant, Melbourne, Australia (400 meters × 80 meters, 6000 trees)

6000 trees of an endangered species with varying heights at maturity were planted into five spirals by the artist, creating a step pyramid for each spiral when the trees are fullgrown. The trees help alleviate serious land erosion and desertification threatening Australia.

What ecological history is contained in the southwest Frisian landscape that REST calls home? As with most places in the Netherlands, the landscape here is a cultural entity defined by the interconnection of the human and the non-human. Consequently, a landscape constitutes a historical record of our dominant beliefs, values, and ideas. The farmland was reclaimed in 1632, the woods were planted by an Amsterdam regent family in the 18th century, and, in 1932, after a part of the Zuiderzee was closed off, the IJsselmeer was born. Only the rolling landscape, cliffs and lakes are naturally formed, courtesy of the workings of massive glaciers during the Saale glaciation. How does one listen to a landscape and understand its message?

Traveling, moving, transporting, building.

The exhibition Two Hectare originates from the site occupied by REST, which is located at a focal point of various communities that move through and across the boundaries of the land: plants, animals, cultures, administrative layers, and people. It is a land shaped by countless geological, planning, and biological influences exerting their force locally, nationally, and globally. The site additionally encompasses a whole series of seemingly contradictory opposites, including history and modernity, natural and artificial, and local and international. Thus, an intimate understanding of the interconnections between the various communities is crucial to forming an understanding of the landscape where REST is located.

Yoko Ono

Water Piece

Steal a moon on the water with a bucket.

Keep stealing until no moon is seen on

the water.

1964 spring

— Yoko Ono, Grapefruit. A Book of Instruction and Drawings, 1964/1970

From a distance, I spot the roof poking out of the landscape. It glistens brightly in the sunlight as though decked in a thick layer of snow. REST is located behind a dike with a road atop it. The cars and cyclists traveling along the road stand out against the bright blue sky, and could be mistaken for pictograms. To get to the farm, you take a right turn just before the road on the dike begins. From this vantage point, it’s hard to make out what’s behind the dike. It’s water, of course, but you can’t actually see that.

It’s March and this is my second visit, following the first one in winter. March is one of those transitional months, in which nothing’s as yet pronounced, and things are still somewhat colorless and capricious, but signs of the new season’s awakening are nonetheless in evidence. Hares dart hither and thither as they chase each other through the grass. The yard is full of daffodils buds, some already bloomed, adding the first splash of color to the landscape. You need time to see any work to fruition here. To plant something in the ground, wait for it to take root and grow, and return every year at about the same time.

The silence amplifies every sound. Rustling reeds, chirping starlings, a car thundering across the cattle grid in front of the dike. But also those that appear to come from the earth. I inadvertently step on a pebble, which shoots into the grass. The wind picks up slightly, and keeps rising. In the distance, I spot a kestrel hovering and swear I can hear the rapid beating of its wings. A gaggle of geese flies low overhead. The sounds of this landscape are far from deafening, but you certainly hear them.

We walked back in the twilight through the garden, dewy peonies bent double as if in supplication, and sprinkled with thundery teardrops, gathering carmine shadows. Irises, purple as the sky; and scarlet poppies with blue-black interiors burst from pods as rumpled as butterflies. Heavily scented pinks lay in abandoned clusters and lupin spires bent under the weight of the day. A scarlet comma stretched its wings in the last patch of sunlight before darting off, up and over the brick wall.

— Derek Jarman, Modern Nature (1991)

Summer solstice: the moment when the sun is at its northernmost position in relation to Earth’s equator. Two Hectare opens on the day with the longest period of daylight. The flowers, plants, and trees on site are at their peak right now. But the landscape can also look a little yellow and barren on account of drought nowadays. Summer, for some, is a period of relative peace and timelessness; for others, it’s the busiest time of year. Farmers, for instance, who cut and harvest the grass in summer and replenish their supplies. Which calendar does REST employ? The seasons of sowing, growing, and harvesting? The rhythm of the art world? Or a greater cycle of growth, breakdown, and decay?

Eeuwigdurende kalender (‘altijdduurende almanach’), anoniem, ca. 1750–ca. 1820, collectie Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam

Kalender met aan linker- en rechterkant de namen van de zes maanden en de sterrenbeelden onder elkaar gegroepeerd. Daartussen bevindt zich een globe op een halve zuil. Bovenaan een verschuifbare strook met tweemaal de dagen van de week. Onder de maanden is een tabel met de zonsop- en -ondergangen gegroepeerd in het korten en langen van de dagen met daartussen een windroos.

For the purpose of Two Hectare, REST has been subdivided into the degrees of a compass. This subdivision of space – with a single focal point and a 360-degree arc – is a reference to the human habit of imposing artificial categories and boundaries on nature, and to the boundlessness of the processes with which the works engage. For the artists and designers, the site functions as a collection of materials, created by both nature and humans. Each of these materials lends itself to demonstrating that everything in the landscape is a narrative entity whose story can take on a different, and sometimes unexpected, meaning when employed in a new composition or form. Clay, for example, which can be found both in the ground around here and in use on the farm, is among the many materials explored and employed in new ways in the exhibition. These works demonstrate that materials, whether natural or man-made, don’t need to be given new lives as they already have them. They ask us to consider a material’s surface appearance as well as that which isn’t immediately apparent.

Digging, sowing, rooting, planting, troweling, plucking, leveling.

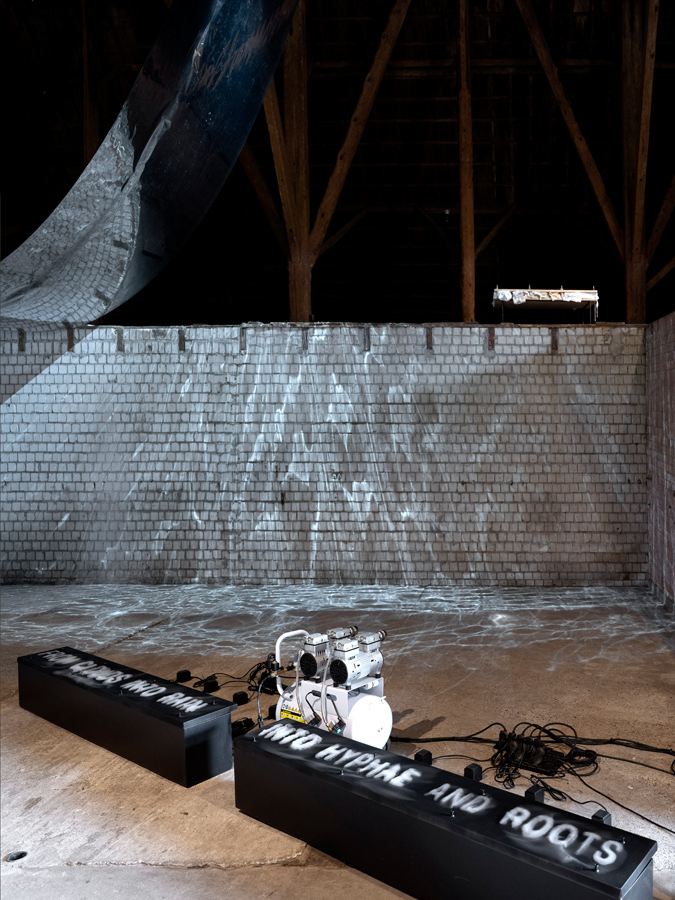

Some of the works focus on processes that take place beneath our feet, unfold in the soil, and thus touch on the following question: What is the reach of the landscape? Is there such a thing as a beginning and an end to a piece of land – to REST? And how can you connect the underground and the aboveground in a meaningful way? These are works that probe, reveal, and map the place, sometimes literally. Others involve elements that more readily come to mind when we consider our natural surroundings, such as water, air, and the sky, which their makers try to ‘capture’ in a variety of created forms and thereby lend shape. Some of these efforts employ technological processes, such as writing with water vapor. Others operate by simulating weather conditions or natural phenomena, for instance by allowing the wind to animate a monumental canvas and thereby cast reflective patterns in the dark. These are works that highlight humanity’s relationship with the natural environment by allowing elements of nature to take their course in a controlled manner. Other creators have pondered new ways of processing and employing materials found in the landscape or remnants from the historic farmhouse. For example, clothes that were worn while mapping the vegetation on the farm have been repurposed as new material, and bricks from the foundation of the old farmhouse have been rearranged into a spatial and functional feature of the landscape. REST operates as a sort of independent grassroots organization located in the countryside, and in doing so contributes to the cultural infrastructure of its area. As a product of this operation, Two Hectare demonstrates that a rural landscape may well be the ideal setting for bringing certain works to life – or for them to live in.

Coordinating, archiving, facilitating, listening, administering.

The grounds of REST have been shaped by a wide variety of developments, among which the presence and operation of the Afsluitdijk, which has had a huge influence on the region as a whole. This symbol of modernity may be a necessary protection against flooding, but its construction signaled the end of the Zuiderzee and its ecosystem. What remains is a coast without a sea and memories of traditional ways of crafts and life. This change is a perfect demonstration of the way the local is always shaped by larger power structures. REST is therefore not just a physical space but also a symbolic one that extends beyond its physical boundaries. It is a place where the local and the global, the personal and the collective, and the past and future converge.

Two Hectare can be approached, understood and engaged with as a channel for a variety of voices. A local ecologist explains the construction of a nature reserve, an artist reflects on the divide between organisms and technology, a sailmaker contemplates the importance of wind, a textile designer reflects on meteorological history as manifested in the weather, a sediment archaeologist lays bare the evolution of the landscape over the past millennia. Through its facilitation of the interaction of these parallel perspectives, REST allows the landscape and its elements to tell a story of adaptation, resistance, recovery, and development, and do so in their natural environment.